Archive (previous posts)

Entry #6 (5-27-2016)

The pool is dry! I knew this day would come eventually (it is a "vernal" pool after all). This was the earliest I've seen this particular pool dry up. It is sad on one level because many tadpoles and smallmouthed salamanders did perish. One year there were thousands that didn't make it. The hope is that enough do make it to adult hood to live a long life and propagate the species so it continues on.

Some macroinvertebrates have flown away to find other bodies of water (there is a creek not far) while others double down that the rains will return one day as they lay in a form of hibernation or in an egg that is drought resistant. As the plants get taller the pool dries quicker. It will refill again this year and may dry again as well. The past several years I've monitored it, it has had much frozen water in January. It will be interesting to see if a fall monitoring trip yields any different species or number.

When a vernal pool is dry it is most susceptible to destruction by developers or land owners who don't care or don't know. To impact a wetland you need to get a permit from the Ohio EPA and possible the US Army Corp of Engineers. Unfortunately, Ohio has lost more than 90% of our original wetlands. The ones that are "replacement" wetlands for the ones impacted are more than not low quality. It is a shame that those that try to stop the destruction are sometimes bad mouthed as extremists. After all, if wetlands help with water supply wouldn't those that impact that be the extremists?

Entry #5 (4-1,2-2016)

A lot of updates here:

Why clean off your equipment after visiting a vernal pool or other wetland? It takes time and it’s only going to get dirty again. Well, unfortunately, one of the draw backs of our mobile society is the spread of pathogens that can cause major devastation (not exaggerating). We know that many bats in the U.S. suffer from White Nose Syndrome which has wiped out whole colonies. On the amphibian front, the chytrid virus, Bsal, and Ranavirus. By cleaning off your equipment you can help stop and/or slow the spread of these devastating forces. Below are instructions on how you can clean your stuff.

Have one or two large containers that you can dip your boots into. One container should contain a solution of water and bleach; the other only water. First, scrape/brush off excess mud and dirt. Second, dip and scrub the boots in the solution. Once thoroughly scrubbed, rinse them off and let air dry. For the solution, the Northeast Amphibian and Reptile Conservation group recommends 3% bleach solution to inactivate the bad stuff. When done, dump the water out (but make sure you aren’t near a waterwayor sewer). You can do the same for the dipnet, microscope slides, etc. Once you make it part of your routine, it takes no time at all. Cleaning off equipment also helps reduce the forward momentum of other invasives as well.

I had a great opportunity to lead a night time tour with a small group to the Sawmill Wetlands. I do want to give a shout out to Ohio Div. of Natural Resources for issuing me a permit. Even though it is in middle of development hell, it gets pretty dark in there! Taking a step off the boardwalk into the water is a step back in time. Fairy shrimp, water mites, copepods, mosquito larva, ostracods, the list goes on. Species that have been here for eons. Shining the light into the water at first reveals detritus and tea colored water (due to the tannin in the oak leaves). But then we see the curious, slow swimming fairy shrimp. We scooped her up, put her on a plastic spool (with some water) and shot the video below. A closer inspection reveals that she is pregnant-a momma fairy shrimp! Papa fairy shrimp is no doubt part of the nutrients at this point (male dies after mating). After her time in the spotlight (literally and figuratively) we gently place her back into the pool to enjoy the rest of the night.

Another creature of the night came into view of the flashlight and that was the water scorpion. Don’t let the name fool you. They are not related to scorpions and don’t really bite or pinch. However, mosquito larva, mites, and phantom midges look out. The water scorpion will capture them with its vice-like grip and pierce their body. What comes next is straight out of horror 101; it injects enzymes that dissolve the soft tissue and then it slurps it up (kind of like a horrific slurpee). The water scorpion is an ambush predator. It sits motionless with its tail (actually a filament to get oxygen) slightly poking through the surface of the water.

We examined some other macros under the microscope; it is really amazing to see how detailed these creatures are, something that can only be done under magnification. After all this we decided to call it a night. As I exit the parking lot I wonder how many of the people in the area know how cool Sawmill Wetlands is.

Post Script: A quick update on Daphnia Pool; smallmouthed salamanders larva are out and about! Check out the balancers (one shown) on this tiny amphibian. After a short while they will either fall off or get absorbed. Go team smallmouthed!

Female fairy shrimp in a spoon (she's pregnant!) (make sure you chose the HD quality setting)

Long arms of the water scorpion.

Here is a smallmouthed salamander larvae. Even has it's balancers!

Decent sized crayfish. Not sure if it is the invasive kind or not.

Below is the daphnia pool--vegetation starting to take shape.

Entry #4 (3-10,13-2016)

A once a year an event unfolds every spring. No matter if you’ve seen it once or dozens of times it is awe-inspiring. On the first warm (55F or warmer), rainy night in spring a mass migration happens right here in Ohio. While most Ohioans sleep there is a silent army of millions of spotted salamanders throughout the state that dig their way out of burrows and from under logs and rocks to crawl to (most likely) their vernal pool.

My partner (who proofs my posts to make them sound good—thank you Meredith!) and I got word that a last minute tour of Glacier Ridge MetroPark was happening. We hopped in our car and made the 35 minute journey. We were not disappointed. Hundreds (or thousands?) of spring peepers were calling away. Easily recognizable by their “X” on the back and only about an inch in length, they can be heard from more than a half a mile away. Put a bunch together and they are deafening. It kind of reminds me of a space ship landing or taking off. As we marched deeper into the park with 30 of our closest friends (and excellent, knowledgeable staff at Glacier Ridge) we were met with a spotted salamander. You can’t mistake this salamander species for any other. In fact the spots on a spotted salamander are unique to that individual—kind of like a fingerprint.

Spotteds head to the vernal pool to mate. The male lays down spermatophores and does his salamander dance for the ladies. He tries to entice his special lady friend to crawl over a spermatophore and pick it up with her cloaca. After internal fertilization the female will lay egg masses on twigs and leaves in the pool. Wait a couple weeks and you have dragon-like larvae that eat a lot.

Western chorus frogs and northern leopard frogs also shared the night. Each species is fitting into a niche in an ancient ritual that goes back thousands of years, all right here in Ohio.

A few days later I headed back to the Daphnia pool (after I disinfected my gear). Things are getting bigger and some things are disappearing! The daphnia are not as numerous, but the ones that remain are large. The ostracods seem to be taking over. The water scavenger beetles are emerging and hardly take a break—always on the move. I also stumble across the first mosquito larva of the season. I can hear you booing. While they are annoying and the females suck our blood (but it’s for their eggs!), they do provide a food source for salamander larvae, predaceous water beetles, backswimmers, and a host of other animals.

After a couple more dips of the observation tray I decide to call it a day. I bid my wetland friend adieu until next time.

We used red film over the flashlights to minimize the impact on the spotteds. This one looks like an alien space ship is about to land on it.

Below is video I took a few years ago regarding the "running of the 'manders."

Below is a photo of a spring peeper from last Thursday night; the picture below that is one from a year or so ago.

Beware! Below are the dreaded mosquito larva!

Below is an ostracod in a drop of water.

Below is the daphnia pool.

Entry #3 (3-5-2016)

I took a break from the daphnia pool and partook in the “Sawmill Saturday” hosted by Friends of Sawmill Wetlands. If you don’t know about these famous wetlands located in Franklin County you should check out the groups’ Facebook page. Many groups, including the Ohio Environmental Council, came together to protect this emerald jewel from the concrete jungle that surrounds it. The night before I went up there I disinfected my gear (I’ll have a future post about that) so as to not spread any undesirables.

The morning was brisk but sunny. I set up my vernal pool “observation station,” which is a fancy way of saying a table, microscope, and aquarium. Then I took a dive (well, a step) into the pool. I scooped up water with the observation stray and filled the aquarium. Didn’t look like much. But you see, that is the thing about vernal pool life; you think there is nothing there, but after your eyes adjust you start seeing the dozens or hundreds of tiny life forms that are now motoring and skipping around in the tray.

I start taking them out to look at under the microscope. To really appreciate the complex body structures and the kaleidoscope of color some of these animals have, you really need to look at them through a microscope. A quick side note, for great photos of macros check out John LeVelle’s blog.

As I’m talking with Alistair—a Friends stalwart—I decide to put the water back and get new water. But wait; there looks like a daphnia swimming but not in that characteristic manner. Lo and behold it is a baby fairy shrimp! We were like kids at a birthday party. They call them “fairy shrimp” because they seem to appear out of nowhere like woodland fairies; shrimp because, well, they kind of look like brine shrimp. You could fill a book on how cool these friends are. They swim upside down with their 11 pairs of legs through the water feeding on tiny particles of algae and plankton. When young, they use their antennae to propel through the water. Their eggs (called “cysts”) can be viable for more than a decade and withstand extreme heat and cold. A mesmerizing creature indeed. In three weeks’ time they will be about an inch long.

As the event/morning drew on, many folks arrived. Children loved the fairy shrimp and some thought the water mite was “gross.” Indeed the mite has some public relations work it should do. Copepods grasped the imagination of young people and an aquatic worm was mesmerizing and creepy at the same time. Fingernail clams quietly lay on the bottom living out their life and watching the amazing world above.

I gently put the treasure back into the pool and am thrust back into the concrete jungle, but have happy thoughts of fairies dancing in my head.

Fairy shrimp under the microscope. This baby fairy shrimp was less than .25 centimeters in length.

This is what they look like when they are all grown up.

Here is a fingernail clam (the video and still are one).

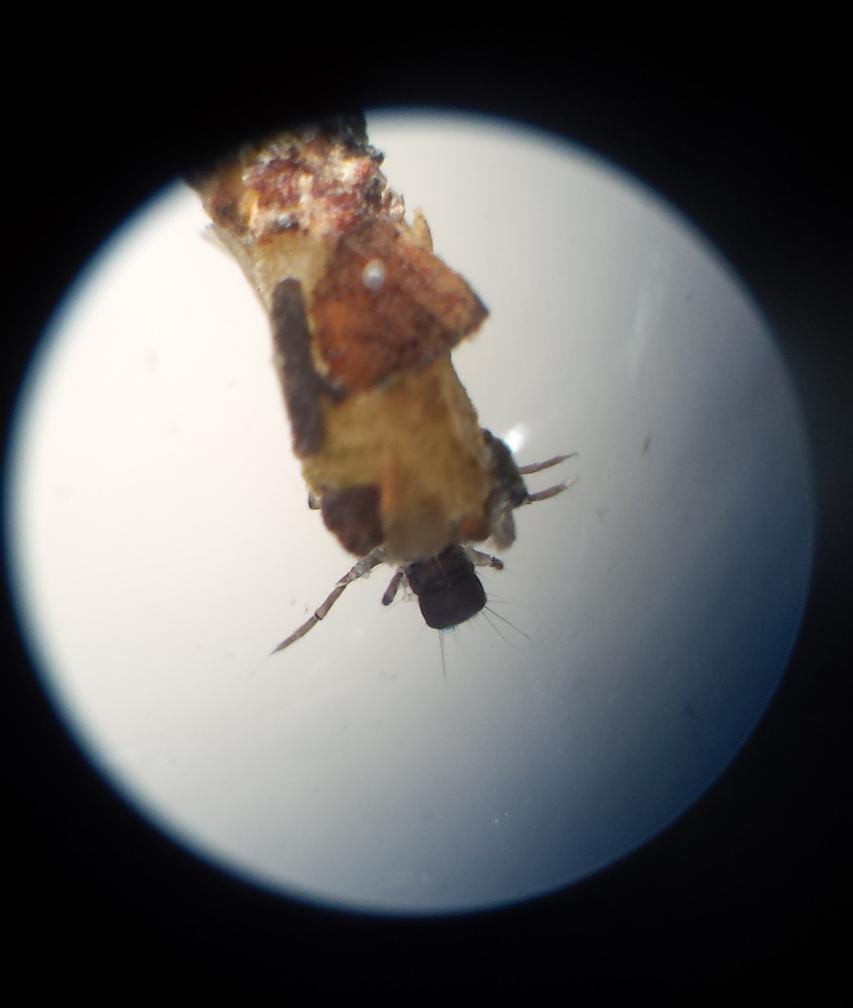

Springtails are pretty cool. They are very tiny and have a furcula that acts as a spring that propels them forward. It is located on the stomach area. They also have large antennae (this one looks like a cartoonish villian with mustache).

Entry #2 (2-21-2016)

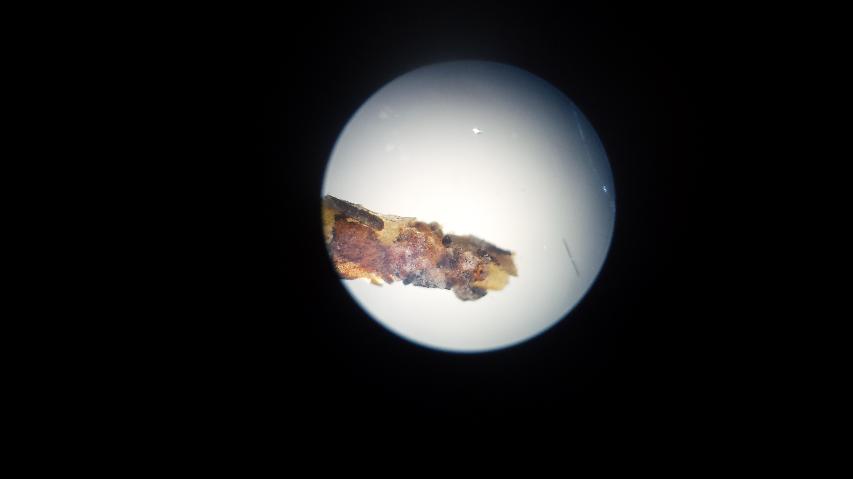

The ice is still grasping to hold its claim-the vernal pool. It is a losing battle given the warm temperatures we are having. The ice continues to transform into a venue for many life forms. Even ones measured in the millimeters such as baby copepods. I was surprised when I peered into the observation tray to see what looked like tiny sticks moving. It was two caddisfly larva! It took me a while to find them because they were about 2 centimeters in length and construct their home out or twigs, leaves, and substrate. They hold their home in place with two “hooks” that are at the end of its abdomen. When freaked out they retreat back into this home. Kind of a bug version of a snail; only caddisfly larva move faster and transform into a flying fly.

The daphnia continue their march to larger and larger size. Did you know they give birth to live young that look like miniature adults? Part of the 1001 things that are cool about vernal pools. Speaking of which, the student that is helping me monitor this vernal pool spotted the first ostracod of the season (that we saw). No more than a quarter of a centimeter in length (at least the one we looked at under the scope), this one species out of 400 known copepod species. They have a very quick and funny movement. If they were to have a sound track it’d be to Benny Hill. How do they survive a vernal pool with no water? They lay eggs that are drought resistant. To best view these macroinvertebrates I use a Wolf field microscope with a 5X lens. I’ve tried hand magnifying glasses, but haven’t had luck.

We also saw the smooth movement of the planeria. What did we hear in the distance? It sounded like a finger running over the teeth of a comb. Must be hearing things. We continue our scooping up water with the observation tray and some old fashion dip netting. Then we hear it again. Holy cow-it is a western chorus frog! A tell-tale sign is their call which sounds like a finger over the teeth of the comb.

It is a fool’s errand to look for one lone frog calling in the day time. We’d have better luck looking for a needle in a haystack.

Shortly after the frog call and with the sun being embraced by the tops of the trees, we decide to pack it in and walk up the hill to the cars.

Caddisfly larva in a spoon and under the microscope (below photos a short video clip).

Planera photo and video (video shot a previous year at this vernal pool).

Ostracod under the microscope.

Entry #1 (2-6-2016)

As winter re-establishes itself this week, there is another world beginning to take shape. A world where water and ice dance between life and death. A world where an organism’s decision can mean a full meal or missed lunch. This world is known as a vernal pool, or seasonal wetland.

This year I’ll be blogging my vernal pool observations of at least one vernal pool in northeast Franklin County. I’ll call it Daphnia pool, because there are lots of daphnia (more on that in a second).

On Feb. 6th in the afternoon I pulled up the wading boots, packed my camera, magnifying glass, observation tray, microscope and accessories and made a short trek down a hill and brush to the pool. I didn’t know what to expect—I guessed there wouldn’t be that much water due to the lack of snow. As the forest line came into view the reflection of clouds and darkness shone at me. There was a good foot and a half of water! Two-thirds frozen, one-third free of ice, but 100% cool.

The ice was not thick around the edge and I stepped through it, collected water in one fell swoop with the observation tray and pulled up several prizes. Daphnia, water mites, copepods, chironomid midges, planaria, and a scavenger beetle. Not bad for an early February dip. The ice is a critical factor in vernal pools. It protects small creatures like daphnia from being gobbled up by water fowl and other predators. The result is hundreds of thousands of these tiny (<.5cm length) buggers propelling through the water with their antennae. This motion pushes water through their carapace and they filter out even tinier creatures. They are also on the main course for other insects as they emerge from the doldrums of winter. Fingers crossed the photos will reveal what species of daphnia. Daphnia photo below. It has little embryos that are pretty well developed.

Above is a daphnia in a plastic spoon (no, I didn't eat it:)

The other macroinvertebrates (invertebrates that can be seen with the naked eye) like the copepods and water mites need magnification to really appreciate their intricacies.

As the season gets going the water mites will move into different stages of development (the lucky ones); the copepods will continue to grow in numbers and size; daphnia populations will rise and fall; and other animals will make their presence known. While contemplating all of this as I swap out macroinvertebrates under the microscope, I realize that the wind is picking up, the sun is going down, and my hands are getting very, very cold. So I gently place my tiny friends back into the water and wish them well until next time this alien humanoid enters the realm of the vernal pool.

Copepod with two egg sacs. This image is looking through a microscope.

Water mite (video below the still image).

water scavenger beetle (image and video)